On Creating Indigenous Worlds And Other Kinds Of Futures

Summary:

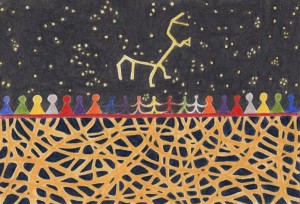

A text on endings of worlds, creating other kinds of worlds, duodji, art, and freedom written by Jenni Laiti is published in English and Finnish. The text is illustrated by tulluk (@uruhuj).

“We know the difference between the reality of freedom and the illusion of freedom. There is a way to live with the Earth and a way not to live with the Earth. We choose the way of the Earth.” – John Trudell

DEAD GREEN FUTURES

Colonialism killed, destroyed and wiped out the Sámi worlds and our people many times over. Our lands, our rivers, our lakes, our traditional livelihoods, our forests. Captured many of us. Enforced assimilation robbed us of our languages, our cultures, and our ways of thinking. Our futures and our pasts. Someone escaped. Some went out of reach. Some couldn't cope. Some fought and believed in the future, others did not. Some survived, most not whole.

From early childhood, we are taught to survive the harsh winters, blizzards, deforestation, climate change, biodiversity loss, mass extinctions, the loss of our languages, and countless other tragic world endings. It is a wonder that we outlasted the apocalypses of colonialism. We have survived because we are part of the land, and the land is part of us. We have survived because we nurture the ecosystem and its rich diversity of life. We have survived because we are committed to preserving life. We survived because we loved and cared for life because what you love, you do not destroy.

There is no green future in sight, because green colonial futures are dead, black and grey futures for us. They do not speak the language of our land, they do not understand the speech of our rivers and cannot listen to the wishes of our winds. Green transition wind farms, dams and mines in Sápmi will destroy our land, our rivers and our wind. Killing the Earth to protect it is the most devastating so-called solution to the climate emergency and environmental crisis. Amid the ruins of colonialism, we Sámi continue creating new worlds every day by protecting and nurturing the Earth’s diversity. We persevere because we know that our own wellbeing and survival are inextricably tied to the wellbeing of the Earth. We Sámi and the world’s other Indigenous peoples conserve eighty per cent of the Earth’s remaining biodiversity, and in doing so, we sustain the diversity of all existence and protect nothing less than life itself.

FREEDOM MEANS LOVE

Mun gulan Anárjohkii. I belong to Anárjohka, to my ancestral river.

One of the most beautiful things in life is to belong somewhere and to feel part of a community. In my language, Northern Sámi, we introduce ourselves by stating where we belong. Gullat means ‘to hear’, ‘to belong’, ‘to understand’, ‘to feel’, ‘to touch’, ‘to be meant for’, and ‘to be from somewhere’. The close linguistic link between ‘belonging’ and ‘hearing’ invokes the dialogic bond that connects the people and the land. We see ourselves not as owning our land, but as belonging to it, and to our community, and the whole, as reflected by the derivative verb gulahallat, meaning ‘to converse’, ‘to communicate’, ‘to hear across a distance’, ‘to understand one another’, ‘to make sense of one another’s speech’, and ‘to exchange news’.

For the Sámi, freedom can only exist in the collective, because there is no real freedom in being severed from the greater oneness to which we belong. To be free means to belong to the land, to a region, a place, a family, a clan, a community and a nation. We are free only when loving bonds tie us to our land and community, as evoked by the words ‘freedom’ and ‘friend’, which share the same Indo-European root: fri, meaning ‘love’.

Freedom is a utopia that exists in the collective mind and body. It resides in past lives, ancestors, traditional lands and future generations. When a river is dammed, reindeer grazing lands are logged bare, and salmon no longer return to their native rivers to spawn, our spiritual and physical ties with the land are broken. We Sámi are connected to our land in mind, body and spirit, because we are inseparable from the land to which we belong.

For me and many others, the struggle to cast off the shackles of colonialism has been a lifelong fight for self-determination over our bodies, thoughts, language, land, futures and destinies. A life that amounts to more than just a daily struggle to cope and survive, a life that is free both in theory and practice. Freedom for me is creating new worlds with art and duodji (traditional Sámi handicrafts), freedom is loving and belonging, freedom is learning, unlearning and relearning and in moments of life and death, where nothing more is more important than the land.

ON LIVING BEAUTIFULLY

"Beautiful duodji items must, of course, be crafted with beauty. But when duodji is fit for purpose and functional, it is beautiful at its most. Materials adorn the craft." – Ilmari Laiti, 2018.

Eallit čábbát is the Sámi philosophy of the aesthetics of good living. In eallit čábbát, art as an isolated phenomenon is a foreign concept, as art is synonymous with a holistic way of life. Life is art, and everyone is an artist. Living beautifully means living a good life in reciprocity and balance with all existence. In everything we do, we strive to live beautifully. In Sámi culture, duodji crafts are intrinsically linked to surviving the Arctic winters, where duodji was created only out of necessity, and everything was made for a purpose.

According to my father, Ilmari Laiti, a duojár, an artisan and master of crafts, beauty is inseparable from functionality in duodji aesthetics. No crafted item is beautiful unless it is useful. When I once asked him what is most beautiful about a gákti (traditional Sámi clothing), he replied that the clothing must be tailored to fit and suit its wearer perfectly. Sámi crafts are always made for a specific purpose and person, reflecting their identity and personality.

The Sámi word duodji means traditional Sámi handicrafts, creative accomplishment or artwork that requires reflection and practice. Duodji culture is the interweaving of distinctive materials, place, the changing seasons, and traditional Sámi knowledges into an expression of life, aesthetics and spirituality. Duodji is the holistic creative embodiment of the Sámi worldview, embracing everything from our language and land to our entire culture. Duodji is an artistic way of being, belonging and communicating with the world. It is a form of social dialogue and nurturing. It is an inherently Sámi form of worldmaking through the creation of beauty.

Sámi knowledge is a body of experiential Indigenous knowledge based on millennia of learning and observation, trial and error, successes and failures. In everything we do, we are guided by our unbreakable bond with the past and future, and by the hope that successive generations of Sámi will inherit what our ancestors have passed down to us. Through duodji, my family, my grandparents, their predecessors and future generations are all connected in a multigenerational chain. In duodji culture, inherited knowledge and skills are united with sensibility to create crafts that embody the place, region and land to which the duojár belongs. Who we are is synonymous with the land we come from.

My aunt Marja-Liisa Laiti is a duojár who says that duodji is always made out of love, never hate. For me, making duodji is a way of communicating with love and compassion. My uncle, duojár Petteri Laiti’s practice is guided by the principle of “gieđain guldala”, or “listening with his hands” to find out what his materials need and want to become. Respect, consent, trust, openness, integrity and mutual understanding are integral to the process. The crafted item must be given time and space to emerge and evolve into its intended form. A duodji item is a living object with its spirit, its own will, its own life, and its purpose.

The duojár’s frugal use of materials is rooted in Sámi futurism and the hope that successive generations of Sámi will be able to continue living on Sámi lands. This crafting philosophy is best expressed in the saying “váldit dušše dan maid dárbbaša” – “take only what you need”. As explained by duojár Per Isak Juuso, sustainability is intrinsic to Sámi duodji insofar as every item is consciously crafted to last over a hundred years, and during its century-long lifespan duodji can be adapted, repaired and repurposed. What new futures might emerge if everything was made from love and beauty to last forever?

The Sámi aesthetic finds expression not only in our crafts, but in lived lives, bodies, experiences, identities and movements all of which have been fractured by colonialism. We learn Western aesthetics instead of learning about living beautifully. As a young girl, I can recall bathing in the sauna with my father’s oldest sister, Elle Saijets, who observed my legs and exclaimed “What thick calves you have!” For Elle, born in 1933, thick calves signalled a strong, healthy woman fit for strenuous physical labour – a defining feature of a survivor. Similarly, the oversized, layered clothing worn by our ancestors have been key to survival for all Arctic peoples. Practicality, strength, resilience, and health defined beauty, not just appearance or visual charm.

My own duodji journey has been an ongoing process of learning, struggling, losing my way, searching and discovering. How could we live more fully and holistically in a beautiful way? How do we decolonise the aesthetics of life? How could we understand it in ways other than the Western ways we have learned? Could the aesthetics of life be an essential value in creating a new life, and could it be one that no one could exploit? How could the aesthetics of life liberate us and be a value of freedom in itself? What can we learn from nature's own beautiful way of living, and what is the Sámi aesthetic in the ends of the worlds and in the beginnings of the new worlds?

THE MOST PRACTICAL OF UTOPIAS

Endings of worlds and beginnings of other kinds of worlds occur sequentially, overlapping, woven into each other and simultaneously. When this world is gone, what will follow? Where will it exist? What will it be like? How will we get there, and how will we live there? What would you do there, and what would you bring with you? I have already packed everything I need: my river, my boat, and fish.

For people before us, creating worlds was a way of sustaining life. They made everything they needed themselves. They caught and hunted their own food, clothed themselves, built their own shelters, made tools for hunting, fishing and transportation, taught their children, and had their own system of governance, beliefs, culture, language, economics, social services, community relations, history, literature, art and networks of coexistence – a whole world of their own.

Colonialism invaded our world about four hundred years ago, starting a slow process of destruction that annihilated our culture piece by piece, the end of one world after another. Despite the many endings we have endured, we are still here, because we have kept repairing and nurturing all the things colonialism broke. We kept building new worlds, every single day. We learned about resilience, adaptability and survival. We held fast to our ties with past and future generations in our dual role as apocalypse survivors and builders of other kinds of worlds, both visible and invisible ones.

Sámi worlding is a radical form of Indigenous futurism. It is a creative form of self-determination, freedom and aesthetics aimed at safeguarding the future for the next seven generations. It centres on reciprocity, caring, sharing, loving and living beautifully. It consists of reimagining, rebuilding, singing, dancing, making art, activism, keeping alive our language, revitalizing our languages, writing and reading books, and telling stories about alternative futures. Creating worlds is the defence of life and its meaningfulness. It honours the eternal will, instinct and aspiration of all living beings to sustain life and its biodiversity. When worlds approach their end, it is crucial for the survival of both humanity and all existence that we continue to imagine, dream, envision, and sow the seeds of alternative futures.

Worldmaking is dreaming and wonder and dreaming, over and over again. It is the slow work of accumulating tacit knowledge. It is a bold, visionary, fearless futuristic practice. It is a process of learning, reiteration, practising and reimagining. Through repetition and rehearsal, it becomes part of who and what we are. It is friendship, companionship, and collaboration. It is togetherness in listening, questioning, and sensitivity. It encompasses everything: giving life, pain and hardship, grief, love, transformation, adaptation and survival, living and dying.

Asking for consent is a common courtesy in Sámi culture. When consent is sought, all forms of cooperation can proceed responsibly, respectfully, fairly and lovingly. Consent is required for everything you do. It requires patience and the ability to listen. Creating worlds requires asking for permission and consent also from the future, as the purpose is to collaborate together with the future, not colonize it. What kind of future does the future want for itself, and in what kind of reality do future generations wish to live? What alternative futures can we imagine, and how could we still be here, on Earth, for the next thousand years?

For me, world creation is an aesthetic of life that reflects 10,000 years of lived life in Sápmi. In my practice, I travel backwards and forwards in time, from one world to the next, changing form, and as I change, so does the world around me and my mode of being in the world. When I make art with the river, I become the river. When I collaborate with the land, I myself become the land. I metamorphose into life, stones, trees, forests. I become not only the fish but also the river in which it swims. I become not only the tree, but the entire forest. I become the earth, the air, the entirety of the universe. Creating worlds commits one to being a companion, a friend, an ancestor, a grandchild, a snowy owl, the land, Teno River, a salmon, permafrost, a glacier buttercup. Worlding is not about me or my visions, my accomplishments, but a form of reciprocity, a communal practice of thinking and working together, discussing, coexisting and dreaming with other living beings.

Worldmaking is the most practical of utopias. It enables the manifestation and realization of dreams that would otherwise be impossible to create into this world. In 2017, a group of Sámi activists called Ellos Deatnu (Long Live Deatnu River) declared a moratorium in the island of Čearretsuolu, suspending the enforcement of Deatnu River fishing regulations enacted in violation of Indigenous rights. The activists announced that the moratorium would hold firm until the regulations were renegotiated and consent was gained from the local Sámi community. The Ellos Deatnu moratorium is a radical utopia transformed into reality, culminating in the declaration of a sovereign Sámi territory where freedom is practice, practice is vision, and the vision is nothing less than Sámi self-determination.

Creating worlds creates hopes, needs and pathways through which different realities are born into new realities. Speculative reimagining sows the seeds of alternative futures, not as a form of escapism, but as an apocalypse survival strategy enabling us to recognize alternative possibilities. Creating worlds creates a space where we are free to live again and again and again. In this space, through speaking out loud, we create movement, allowing us to catch glimpses or glimmers of hope, from the beginning of a different future. What we feel in our bones today we could only imagine yesterday, and today’s distant whisperings on the wind will ring loud and clear tomorrow.

Indigenous philosopher and author Ailton Krenak writes that in the end of the world, we always have time for one more story. What would be the story to postpone the end of the world and could that story keep us alive? Which story shall I tell: the one about the apocalypse of colonialism, or the one about our ancestors and their travels from one world to another?

On Creating Indigenous Worlds and Other Kind of Futures is published as part of the Indigenous Climate Futures Embassy project supported by Punos and Hosting Lands.

LITERATURE

DEAD GREEN FUTURES

Benally, Klee. (2023). No Spiritual Surrender: Indigenous Anarchy in Defense of the Sacred. Detritus Books.

“Apparently, green futures are still dead futures for Mother Earth.” (p. 202).

“Although they comprise less than 5% of the world population, Indigenous peoples protect 80% of the Earth’s biodiversity in the forests, deserts, grasslands and marine environments in which they have lived for centuries.” What is missed is that ideally, Indigenous peoples protect all of existence – not just percentages.” (p. 201).

FREEDOM MEANS LOVE

Montgomery, Nick & bergman carla. (2017). Joyful Militancy. https://joyfulmilitancy.com/

“Freedom” and “friend” share the same early Indo-European root: fri-, or pri, meaning “love”. A thousand years ago, the Germanic word for “friend” was the present participle of the verb freon, “to love”. This language also had an adjective, *frija-. It meant “free”, as in “not in slavery”, where the reason to avoid slavery was to be among loved ones. Frija meant “beloved, belonging to the circle of one’s beloved friends and family.” (p. 84 - 85).

“Friend” and “free” in English come from the Indo-European root, which conveys the idea of a shared power that grows. Being free and having ties was one and the same thing. I am free because I have ties was one and the same thing. I am free because I have ties, because I am linked to a reality greater than me.” (p. 85)

ON LIVING BEAUTIFULLY

Valkeapää, Nils-Aslak. (1984). Greetings from Lapland. Zed Books.

“Art as an isolated phenomenon is unknown to the Sámi. As a result, artists as a professional group are also a product of modern society, a result of the mad rush of our time. Through the Sámi lifestyle, each moment in life becomes an artistic experience. Carving with a knife, colorful clothes with a belt, a cap and a scarf, white moccasins on the snow, isn’t it a dance, even if the steps may be unsteady from time to time? Isn’t it beautiful when folk sit down in the snow, make a fire and gather around the flames?”

Laiti, Jenni. (2012). Doaimmalaš nisu ja almmái nu oalgái. Sámi čábbodatideálaid guorahallamin. Artihkkal Nuorat - áviissas.

“Gávdnen iežan dutkamušas, ahte dološ sámi gándaideálii gulai leat čeahppi suhkat ja njoarostallat. Čábbodat meroštallui sávrivuođain ja gievravuođain ja das lei stáhtus. Dolin čába nisu lei jorbbas ja das ledje rukses muođut. Ruoinnas olmmoš lei mearka buohcci olbmos, muhto jorbalágan áhkku lei fidnen doarvái biepmu. Mo olmmoš lihkada de dat váikkuha čábbodaga árvvoštallamii. Oppalaččat sápmelaččaid čábbodatáddejupmi lea rievdan viehka ollu maŋemuš 50 jagi siste ja leat lahkonan oarjemáilmmi oainnuid ja árvvuid.” - Yngve Johansen

THE MOST PRACTICAL OF UTOPIAS

Simpson, Betasamosake Leanne. (2017). As we have always done. Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

“This is the foundation of our self-determination and freedom – producing everything we need in our families within grounded normativity within a network of caring and sharing. We made our food, our clothes, our homes, we made our education system, our health care system, our political system. We made technology and infrastructure and the systems of ethics that governed its use. We made our social services, our communication system, our histories, literatures, and art.” (p. 80).

Krenak, Ailton. (2020). Ideas to Postpone the End of the World. House of Anansi Press.

“My main reason for postponing the end of the world is so we have always got time for one more story. If we can make time for that then we will be forever putting off the world’s demise.” (p. 36).

INTERVIEWS

Ilmari Laiti, Petteri Laiti and Marja-Liisa Laiti. 2018.

Per-Isak Juuso. 2019.